Financial Centres’ Polyarchy and

Competitiveness

Does Political Participation Change a Financial Centre’s

Competitiveness?

Bryane Michael

University of Oxford

Bertrand Candelon

University Maastricht and Université Catholique de Louvain

Abstract

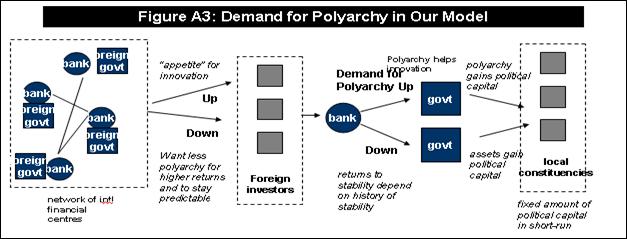

What role does polyarchy (and thus increased democracy) play in aiding the development of an international financial centre? We find support for decades of theorising that some jurisdictions use autocracy (less polyarchy) to help grow out their financial centres. We look at the growth of these financial centres as the extent to which they attract more funds from abroad (cross-border bank liabilities). Polyarchy decreases as other international financial centres’ centrality in the global financial centre network expands. Polyarchy increases in most jurisdictions over time because some financial centres rely on increasingly polyartic governance as a way to foster financial innovation through increased participation by non-previously powerful sectors. Namely, the growth of an international financial centre’s centrality in global financial networks relies on tapping down on polyarchy. Yet, such polyarchy – when used by some very central jurisdictions to remain central – “spreads.” We model such a relationship between polyarchy and centrality in the global financial network, describing even the most complex quantitative analysis in a way a non-specialist can understand. These results could impact decisions ranging from Brexit to Hong Kong’s autonomy in its post-2047 period.

Keywords: international financial centres, endogenous global city network centrality, dynamic polyarchy, finance juntas, financial competitiveness, Bayesian network analysis.

JEL Codes: D72, F55, F33, P48

We acknowledge the Hong Kong University Grant Council’s

Theme-Based Research Scheme for partially funding this research under the

research programme Enhancing Hong Kong's Future as a Leading International

Financial Centre. We also acknowledge support from the Europlace Institute

of Finance and Insti7 programme Risk Management, Investment Strategies and

Financial Stability. All ideas, as well as any omissions and mistakes,

remain our own. We do not claim to represent the views of any institutions we

affiliate with, and nothing in this paper represents investment advice. Co-authors

have worked on separate sections of the paper (as a multi-disciplinary

project), thus each co-author may not necessarily agree with all the material

in the paper.

Contents

The Blundering Literature on Political Institutions and

International Financial Centres

From regressions on democracy to political cycles

Looking for democratic/polyartic cycles as politicians

promise more foreign investment

The Stylized Facts: The Link between Democratic Inclusion

and Financial Centre Competitiveness

Democracy in Y/Zen’s top international financial centres

Polyarchy and international financial centres

Modelling and Operationalizing Endogenous Change in IFC

Politics and Competitiveness

Changes Within and Between Countries

The Data and Empirical Methods We Used

Jurisdictions, raw polyarchy and network centralities

Getting polyarchy and network centralities ready for

analysis

Does Polyarchy React to a Financial Centre’s Centrality?

How Reliable Are These Results?

Appendix I: A Model of Domestic Political Change and a

Model of Network Change

The micro-foundations of financial assets versus

polyarchy

Supply and demand for polyarchy, innovation and

investment assets

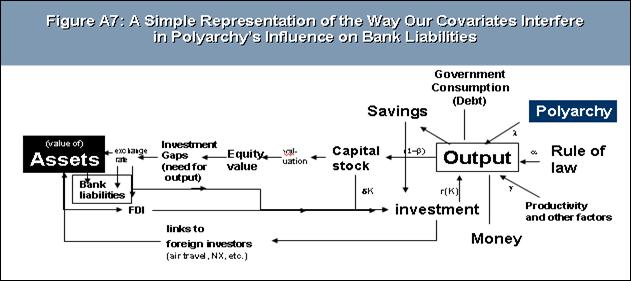

Modelling the interference from covariates

Appendix II: Details of Econometric Procedures and

Results

Fitting

the macro and other factors to the data

Variables used to create network data

Matrix Statistics for Banking Liability Data

Polyarchy and Importance to the Financial Network

Financial Centres’ Polyarchy and

Competitiveness

Does Political Participation Change a Financial Centre’s

Competitiveness?

Bryane Michael, University of Oxford

Bertrand Candelon, University Maastricht and Université Catholique de Louvain

Introduction

Democratic institutions seem antithetical to building world-class international financial centres. Most famously, Shaxson – in his survey of tax havens – notes the extent to which secret cabals in The City (in London), Delaware, Jersey and other places dominated financial services lawmaking.[1] Regulatory capture has resulted in financial regulations which have made several international financial centres far more competitive – if far less robust to crises -- and less consumer-friendly.[2] The need to grow local financial centres into internationally competitive international financial centres has subsumed local politics in many places – resulting in the tacit or explicit restriction of certain political ideas and polities.[3] Even in places not usually considered as financial centres until recently, the design of regulatory institutions has encouraged such capture.[4] Politics -- dominated by elites, specialists and/or special interest groups -- has determined the extent and type of financial regulations in international financial centres.[5] Indeed, some have argued that policies aimed at making an international financial centre more competitive have helped some of these groups stay in power and forestall political rivalry.[6] To what extent does international financial centres’ competitiveness incentivize/enable such restrictions on political pluralism? To what extent does the reverse happen – as restrictions on political participation boost the competitiveness of the financial centres which legitimizes certain politically powerful groups?

Our paper shows that political participation in adjusts to a financial centre’s competitiveness, and that competition between international financial centres affects the extent of such political participation/pluralism in these financial centres. For example, Hong Kong lawmakers and politicians may keep a close eye on how many assets London, New York and Singapore-based asset managers attract from abroad – shutting down groups vying for other interests (like income redistribution) when Hong Kong’s own competitiveness falls. Decisions about political pluralism and financial centre performance seem inexorably linked in leading financial centres, not only within these centres but also between them.[7] Yet, greater political participation/inclusiveness does not always/only reduce the performance/competitiveness of an international financial centre. The inclusion of different ideas and interests does not only drag down performance. As costs and benefits in the international network of financial centres changes, so must individual centres adapt – renewing the services and systems they use to compete globally. Increasingly democratic political institutions help foment these new ideas.[8] Political competition and plurality helps generate new ideas for improving the intermediation of capital, as well as support for the financial centre. As these financial centres attract more assets and thus profits, they have more gains to share among different constituencies who demand rewards for their previous patient silence. When a financial centre reaches a certain size, more polyartic institutions allow the winners to compensate other sectors of society, as well as draw them in into a process for seeking their ideas and political support for new and better ways of competing internationally.[9] Political plurality and international centre competitiveness are thus locked in a dynamic dance across time. Any proposal to reform financial institutions thus needs to match the phase of that dance in order to achieve its desired effects. Policymakers in places like the UK and Hong Kong need not ask whether they should keep or give up greater autonomy over their financial regulation. The main question concerns whether they need to make this adjust right now.

We draw together the data into a conjecture about the way that international financial centres’ competitiveness and polyarchy interact across these centres. We measure such competitiveness as the cross-border assets drawn in by international financial centres’ banks. We use an off-the-shelf measure of polyarchy, as the extent to which more groups affect (or are allowed to affect) policy.[10] We conjecture that these international financial centres need to restrict such polyarchy to pass the narrow financial regulations needed to grow the national financial centre(s).[11] As other financial centres do the same thing – lawmakers, politicians and regulators need new ideas for financial sector regulations that will give them the edge. Such ideas come from the fracas of political competition, from new polities and the need to strike compromises.[12] Yet, polyarchy reduces again as governments of the day need to reduce resistance toward implementing these new ideas.[13]

We structure the paper as follows. First, we review the scant theorising about international financial centre competitiveness (size, growth, market niches and so forth) and their political plurality. Hundreds of political theorists, historians and geographers have written about the way that political interest groups use financial policies to obtain and keep political power. Yet, we could find none looking at the use of these policies at the global level (between financial centres themselves). Second, we look at trends in the raw data before going into our in-depth analysis. These trends set the stage for our main analysis, and should provide the reader with the intuitions and insights needed to assess our later analysis. The third section presents our model – showing how we see the trade-off between innovation and ‘focus’ (for lack of a better word). As usual in economics, jurisdictions have an optimal amount of polyarchy at any given time – polyarchy which helps attract the larger amount of cross-border bank liabilities given the polyarchy and central of other financial centres in global financial centre networks. The fourth section explains our empirical methods, using language simple enough for a non-social scientist to understand.[14] The final section concludes. The appendices offer more quantitative background and support for our analysis.

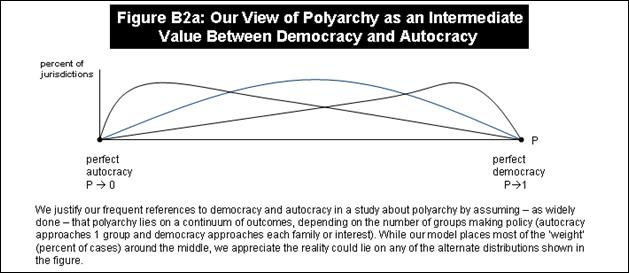

We should caution the reader about some assumptions we make before beginning our argument. First, we must assume that political polyarchy at the ballet box in some way reflects polyarchy of those groups, cabals, juntas, bureaucrats and bankers who make financial policy.[15] We understand the limitations of assuming that Swedish financial interests must vary more than Chinese ones – even though China has far more stakeholder groups interested in the outcomes of financial policy than Sweden has.[16] Even though Saudi Arabia (for example) does not hold open elections often, elite rivalries do shape financial policy, as patrons on behalf of their clients and supporters – and they influence financial policies polyartically at the Cabinet of Ministers and ministerial levels.[17] Where possible, we provide references to previous research showing the usefulness and likely validity of such an assumption on the macro-level. Similarly, albeit more credibly, we hypothesize that when polyarchy decreases, financial regulation reflects the interests of the groups in power. In other words, we do not distinguish between differences in power between groups exercising polyartic power. Nevertheless, we do not assume that the members of a particular polyarchy reflect mostly financial institutions’ interests (indeed we test this proposition in our paper). We may also slip by associating more polyarchy with more democracy – a fact true by definition except when a jurisdiction changes from a position of greater to less democracy (thus becoming more autocratic).[18] We may also slip by talking about V-Dem’s polyarchy measure as a more reliable measure of the polyarchy want to understand than it is.[19]

Our other assumption major assumption deals with the way more polyarchy translates into more financial innovation (or at least competitiveness). We empirically test the extent to which polyarchy correlates with a financial centre’s centrality – particularly for very large and central jurisdictions with rising polyarchy. We theorise that polyarchy’s benefit comes from financial innovation and good ideas from a larger range of society’s stakeholders – rather than from something else. Based on our literature review, this looks like a reasonable assumption.[20] However, we usual refer to this chain of causation, while ignoring other possibilities.[21] To keep our paper at a reasonable length, we do not try to figure out the exact reason why polyarchy might rise after a time of repression, when the financial centre becomes larger.[22]

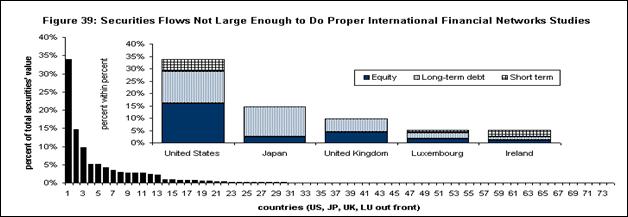

Another assumption concerns our definition of financial centre competitiveness. We equate cross-border banking liabilities with a jurisdiction’s competitiveness. Yet, we use Y/Zen’s list of top international financial centres to choose the jurisdictions to study – a list which most decidedly rejects such a narrow definition.[23] Indeed, as we show later in our paper, cross-border bank liabilities flows differ from the flows of assets, equity, short-term and long-term debt. With some jurisdictions specialising in securitisation, mutual funds, and foreign exchange, our approach captures a microscopic part of this overall competitiveness.[24] We feel justified though in talking about broader competitiveness, as our methodology easily extends to these markets. Many financial centres excel in many financial services at the same time because of their “product complementarities, the nature of local epistemic communities, and regulation.”[25]

Finally, we often must talk about international financial centres (like Frankfort or Paris) using data for their nation-state (Germany and France respectively). For jurisdictions with multiple financial centres -- like the US, China, and Germany – using national polyarchy hardly represents a fair portrayal of polyarchy on Wall Street (New York) versus Sand Hill Road (San Francisco). Doha, Seoul or Tokyo might (or might not) account for most of these jurisdictions’ banking centrality. Lack of data at the city-level forces us to elide entire jurisdictions with the city that appears on Z/Yen’s index of top international financial centres. We try to refer to the country as a whole, rather than individual financial centres – leaving it up to the reader and future researchers as to the extent to which the jurisdiction’s whole represents its parts as metropolitan financial centres.[26]

The

Blundering Literature on Political Institutions and International Financial

Centres

From regressions on democracy to political cycles

None of the studies of international financial centres look directly, quantitatively or econometrically at the way local political institutions respond to the competitiveness of their international financial centres. Did Singapore’s and Lee Kwan Yew’s People’s Action Party’s resistance to outside and variegated political participation help the nation-state’s elites build a world-class financial centre? How much did the politics of Wall Street’s elites drive Ronald Reagan’s liberalisation programme (and his chocking off to participatory policymaking institutions like labour unions’ input into policy)? How much did the need to compete with Tokyo or London also shape the former US President’s decisions? Despite extensive work on measuring and assessing international financial centres, previous studies tend to ignore three aspects of international financial centre competitiveness politics. First, to the extent they empirically/econometrically look at the link between politics and international financial centre competitiveness, they do so through the lens of “democracy.” Second, they ignore the dynamics of political change – and the way that political change drives international financial centre competitiveness. Third, they ignore local politics responds to and affects local politics abroad as these politicians look at the competitiveness of their jurisdictions’ financial institutions.

The first blunder of the literature

consists of a narrow focus on regressions looking at the relationship between democracy

and financial development.[27]

For example, studies like Doces looked at the extent to which differing levels

of a survey indicator designed to proxy the extent/level of ‘democracy’

correlated with levels of foreign direct investment.[28]

Girma and Shortland might find that the degree of democracy (or elite capture

of political decisions) affects financial sector development, as measured by

indicators such as private sector credit-to-GDP ratios, stock market

capitalisation-to-GDP ratios and stock market value traded-to-GDP ratios.[29]

Democracy and “good” political institutions – holding other variables fixed –

aid in financial sector development and thus the likely emergence of

international financial centres.[30]

Yet, the consensus – if one can call it a consensus – finds that democracy

helps promote the development of large financial sectors using measures like

these, only for countries with robust legal and governance institutions in

place.[31]

Democratic development and financial sector/market development have gone together

since the industrial revolution, and will likely continue to do so.[32]

Of course dissenters and hedgers will always remain, given the messy nature of

the world and the data.[33]

The nature of these measures also pose problems, as indicators measuring the extent

to which a country has an autocratic versus democratic governance institutions,

as well as measures which try to measure the durability of those institutions,

remain highly problematic.[34]

Yet, these studies fail in a more fundamental way. They fail to look at

dynamics – how the extent of democracy and self-determination change over time

in response to changing investment needs.[35]

The second blunder of the literature consists of ignoring the dynamics of changing financial sector competitiveness and political participation. Many works – particularly by geographers – talk about cycles of political participation and financial sector competitiveness over time, from an economic, political and sociological perspective. Any study of a financial centre, like Singapore, would show the constant competition with other financial centres, the need for politicians to restrict or expand democratic participation as needed, and the way that such participation affects an international financial centre’s competitiveness.[36] In the US context, scholars and pundits alike see a dichotomy between “democratic participation” in finance and a more centralised one, focused around finance-sector interest groups.[37] Many of these focus on events which depend as much as historical accident as any deliberate policies arising after, or in reaction to, these accidents. Subsequent policy may encourage the development of a financial centre.[38] Yet, few provide a working, testable model of political and financial sector change in international financial centres. Some exceptions do exist.[39] Yet, many describe such accidents as “path dependencies” (meaning we don not know really if their causes can be replicated).[40] Yet, a large literature even exists admonishing academics with quantitative research skills to pay attention to the inter-relationship between politics and finance in the development and growth of these international financial centres...leading to our third blunder.[41]

The third blunder committed by the literature in our subject consists of most discussions tending to depoliticise both the national and international aspects of international financial centres.[42] At their most extreme, models of financial centres see different policies ‘diffusing’ – with financial authorities copying policies from other jurisdictions like the spreading of a fad or hit song.[43] Such diffusion has no room for politics, either within or between jurisdictions. For authors like Hampton and Christensen, the politics of these international financial centres extends only so far as such lobbying (usually targeted at tax havens) help or hurt other – particularly larger – countries like the US.[44] They describe how the IMF, the OECD and even countries like the US call for financial and other reforms in the international financial centres.[45] They draft the rules that countries can follow – or not.[46] Many even argue that international elites use and abuse these centres and their places – in effect usurping their politics.[47] Others argue that local elites manipulate the political process – without ever describing who or how -- to create an international financial centre serving their own interests.[48] These elites’ better understanding of the complexities of finance (better than even national regulators) supposedly facilitate their ability to manipulate the political process and the government itself.[49] If international financial centres do compete, authors like Hall would have us believe that they do so through apolitical government policies.[50] Wang and authors of his ilk present the results of such political machinations and movements as faits accomplis (the inevitable result and cause of “political will”).[51]

Worse still, they ignore the strong political as well as economic harms many of these reforms would cause if local politicians did more than pay these reforms lip service. For these authors, the most that can happen is that, “the cumulative pressures for reform will significantly re-configure the offshore finance industry. Offshore finance may return onshore to the large, functional financial centers such as London or New York.”[52] Such a reshoring would kill many political careers in these centres. Many international financial centres seem to exist to serve as offshore international financial centres – making their success a prime political objective.[53] Authors that claim that such competition simply represents “jurists' and policymakers' attempts to resolve an inherent contradiction between insulated state law and the rapidly integrating world market” have been as misled as these politicians’ constituents into believing financial law represents a non-political, non-competitive ‘policy area.’[54]

To understand the dynamics of political change, given economic/commercial change in an international financial centre, we must turn toward the historical literature. Recent case study and historical treatments of financial centre development have particularly shown the waving and waning nature of democracy and financial sector development. Financial, and thus economic, performance represents a strong electoral issue in many countries – just as electoral results represent strong drivers of international portfolio and direct investment.[55] Politicians and any/all interested parties keep an eye on the rhetoric and policies foreign investors want.[56] Sometimes, such competition between international financial centres may imperil the viability of the policies these jurisdictions have put in place to compete internationally in the first place.[57] While many emerging markets “simply do not exist for global financial market investors,” some financial centres absolutely do.[58] Many of these political and foreign investment decisions follow cycles. Most scholars have assumed that the uncertainty in these cycles drive investment.[59] But what if the decisions taken in these cycles reflect the nature of the cycle itself? Namely, what if disposition toward particular political practices and institutions (particularly democratic ones) cause changes in investment – which in turn – causes changes in political preferences?[60]

Looking for democratic/polyartic cycles as politicians

promise more foreign investment

The British Virgin Islands provides one concrete example, showing how the politics of an international financial centre depend on that centre’s ranking vis-a-vis other centres (and the difficulty of empirically detecting such dependency). Like many of the top international financial centres, the British Virgin Islands (BVI) has inherited a historical focus on international finance due to its position along trading routes and its specialisation in a larger political/economic entity (the British Empire).[61] In the classical telling of BVI’s inherited position as an international financial centre, the jurisdiction – like the other crown dependencies – had served as an extension of the City of London.[62] Like in the Cayman Islands, groups vied for power by giving foreigners tax and other benefits in exchange for bringing their money to the island.[63] Yet, as shown in Figure 1, these policies had less impact then similar policies in the Cayman Islands, Jersey, Bermuda and the other jurisdictions shown in the figure. The BVI’s GDP and employment share of finance hovered at around 10% of GDP at the start of this decade. Doubtlessly, the BVI’s falling behind other financial centres at the time of the global financial crisis, and long before then, influenced the Island’s politicians far more than this sector’s meagre size suggests. The financial sector almost certainly influences local politicians more than its small size to GDP suggests. [64]

In fact, national politicians used the jurisdiction’s nascent financial development as both political end and means. Orlando Smith, at the start of the millennium, intensified the trend already underway of cooperating with business interests, cleaning up corruption, and most prominently working to grow the Island’s offshore financial industry.[65] His National Democratic Party won the 2003 general election (having formed to run in the previous election of 1999). While he and his party did not win the next elections in 2007, they proved instrumental in ratify a new constitution by the time of the 2007 election. True to BVI politics, neither the National Democratic Party, nor the incumbent Virgin Islands Party focused on the development of offshore finance on ideological grounds. Instead, as noted by several commentators, politics has focused on personal connections, charisma and most importantly -- patronage. As such, the new constitutional project did not appear out of some deep-seated philosophical struggle. The effects of the new constitution – and subsequent laws passed under it – included putting foreign investors and financiers at ease by offering protections against arbitrary seizure/nationalisation of their property rights and investments as well as unwelcome interference from the UK.[66] As in other places, foreign politicians fed this internal political dynamic, as these financial centres served their personal and national pecuniary interests.[67]

Yet, even for a small jurisdiction like the BVI, finding any direct link between politics and foreign investment proves difficult. Figure 2 shows the electoral share of the National Democratic Party (NDP), its main rival the Virgin Islands Party (VIP) and portfolio investment from the US and UK.[68] Despite over-whelming support for the VIP around 2007, US investment shrank (with UK investment radically rising). At the beginning of the 2000s and in recent years, the NDP has won elections, coinciding with slower growth (or even shrinkage) of such portfolio investment. The 2004 BVI Business Companies Act came on the books on the NDP’s watch (though fully implemented by the time the VIP won power).[69] Offshore finance – and offshore company registrations – provided about 55% of total government revenues (amounting to a bit over US$187 million) around that time.[70] No matter which political party held power, the BVI represented a “captured state.”[71] The particular party in power mattered far less for the passage of competitive legislation like the 2003 Virgin Islands Special Trusts Act or non-enforcement of due diligence rules than the extent of political competition.[72]

The lack of political competition and thus effective democracy in any international financial centres, has given financial interests very large influence over financial policies. The BVIs do not quite epitomize the state capture attributed to Jersey.[73] Centres like Jersey allow us to witness the way such capture transcends borders – showing the dependence of financial centres’ politics and policies on each other. International services firms’ (like Price Waterhouse and Ernst & Young) push to expand rules enabling financial centres like Jersey show the extent of global pressure on financial centres.[74] Jersey, in this case, clearly reacted to developments in other jurisdictions. Just like Jersey, other financial centres’ politicians point to the BVIs as model, rival and legitmiser.[75]

The lack of effective multi-party democratic decision-making in some places leaves them open to influence from/through these other channels. Politics represents a contest over financial policy – and finance itself.[76] Less vigorous political competition may allow the state capture which promotes the financial sector competitiveness of places like the BVI and Jersey. Yet, preferences for such political competition do not exist in a vacuum.

Economic forces affect the extent of political competition. Figure 3 shows support for a democratic political system in the jurisdictions housing most of the financial centres we study.[77] US and Japanese voters/citizens view democracy less favourably after the global financial crisis. Relatively untouched jurisdictions like Sweden and Hong Kong have had greater support for democracy over time. A simple bar chart does not prove that democratic or polyartic governance responds to changes in economic factors or a jurisdiction’s financial sector’s competitiveness. Yet, preferences for – and responses to – democratic and polyartic governance do change over time in response to economic change and visa versa.[78] What do the data tell us?

The

Stylized Facts: The Link between Democratic Inclusion and Financial Centre

Competitiveness

Democracy in Y/Zen’s top international financial centres

Superficial data show that international financial centres need just the right amount of democracy at just the right time to thrive. Figure 4 shows the most simplistic analysis available – a popular survey-based measure of international financial centres’ competitiveness versus a measure of the extent of democracy in the international financial centres’ jurisdiction.[79] ‘Authoritarian’ (their words, not ours) leaders like China and the United Arab Emirates sit at one end of the spectrum.[80] Legitimacy-by-performance might drive any attempt to create an international financial centre (as authoritarian governments seek to bolster their rule by creating sectors that push up national income).[81] Gibraltar and the Bahamas, as ‘contender democracies,’ sit at the other end of the spectrum.[82] According to this static picture, taken in 2016, the largest number of highly competitive ‘leader’ jurisdictions came from ‘flawed’ democracies. ‘Hybrid democracies’ had the hardest time breaking into the ranks of the international financial centre leaders. Such difficulty probably reflects both their fragility and the resources going into ‘stage managing’ the political/electoral system.[83] Most importantly, different political regimes statistically significantly correspond with a particular type of financial centre.[84] In other words, leader financial centres grow up around democratic governments statistically significantly more often than they do in authoritarian governments.

More specific data seems to show that democracy hurts financial centre competitiveness. Figure 5 moves from comparing categories to comparing numerical measurements of the extent of democracy and the competitiveness of international financial centres. The same rough pattern emerges. From such a static picture, we see that relatively uncompetitive financial centres have all kinds of governments – from the very democratic to the not-so-much. Yet, the most competitive financial centres in the mid-2010s had more democratic governments (as represented by the countries at the top of the pyramid of dots on the right hand side of the figure). Such figures immediately dispel any monolithic theory positing that globalisation somehow leads to the degeneration of democracy.[85] Nothing in these data point to a supposed contradiction between financial globalisation and democracy.[86]

What happens to the odds of an international financial centre becoming more competitive as it becomes more democratic? Figure 6 shows the “risk” of an international financial centre improving its competitiveness ranking for various levels of democracy. For example, international financial centres scoring highly in the 75% to 100% percentile on the democracy scale tend to have lower odds of increasing their rating as an internationally competitive financial centre. Yet, for the 2nd lowest percentile, relatively low levels of democracy correspond with higher odds of becoming more competitive. Such a view contradicts the view of international policy networks as a monolithic structure aimed at pushing financial openness one way or the other.[87] Such a view also contradicts the binary view of democracy as only good or bad for financial centre growth. Clearly, a certain level of democracy corresponds to a certain level of financial centre competitiveness for any particular jurisdiction. [88]

Polyarchy and international financial centres

Polyarchy probably represents a better measure of the extent of political participation in deciding an international financial centre’s policies. Polyarchy describes the rule of multiple groups in a political or decision-making system.[89] A more polyartic political system includes larger numbers of individuals/organisations taking decisions about a jurisdiction’s financial policies/laws, as well as a more even ‘distribution’ of power between these individuals and groups.[90] While many see such a polyarchy as a benign combination of bureaucrats, financial supervisors, financiers themselves, and even consumer activists; others see such rule as the contest for political power which it is.[91] Many authors have argued that an increased role for financial institutions in financial policymaking would necessarily crowd-out and diminish democratic governance – as “researchers on both sides of the Atlantic started expressing concern about the threat to democratic process posed by the emergent corporate form, the potential for collusion allowed by the growing practice of interlocking directorate, and the general concentration of power in the hands of large firms and banks.”[92]

What do the preliminary data show about polyarchy and international financial centre competitiveness? Figures 7 point to a likely balance, or best relationship, between international financial centre competitiveness and polyarchy. Figure 7a shows the relationship between the measure of polyarchy we use in our study and Y/Zen’s simple measure of financial centre competitiveness.[93] While many theories would predict that big financial centres should get bigger, few would predict the decreasing returns to scale seemingly shown in the figure.[94] Such a dependence on size though means we must use special mathematics later to account for these size effects.[95] Figure 7b looks at this same change in IFC competitiveness, compared with the extent of polyarchy in the international financial centres we analyse. The shotgun pattern in the data shows that more polyartic jurisdictions represent both highly competitive and less competitive financial centres. Yet, the wedge we drew in dotted gray lines suggests that no clear pattern seems to exist in these data. In contrast, Figure 7c flips this relationship on its head. The figure shows the change in polyarchy for international financial centres starting with a certain level of competitiveness. Again, a slightly positive pattern seems to exist between democracy and financial competitiveness. Yet, as we saw already, a golden medium or optimal level appears to exist.

Not only does polyarchy and level of IFC vary across jurisdictions, these correlations vary across time. Figures 8 illustrate how the correlation between polyarchy and IFC competitiveness can positively correlate in one year, but negatively correlate in another year. Figure 8a, in particular, shows the correlation coefficients across the jurisdictions we studied for 2007. In these data, IFC competitiveness increases with the extent of polyarchy. Yet, as shown in 8b, the correlation between polyarchy and IFC competitiveness decreases across countries. Such results highlight the variable nature of the relationship between polyarchy and IFC competitiveness. The first impression from these data might point to a positive correlation between polyarchy and IFC competitiveness for lower ranked financial centres, and negative correlations for higher ranked financial centres. If we interpret these data more conservatively, however, we might notice change, without trying to shove the data into a pattern. No matter what you/we think about these data -- polyarchy and IFC competitiveness clearly adjust to each other somehow over time.

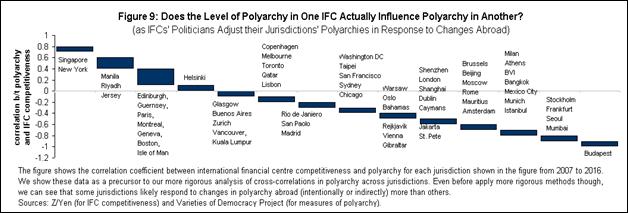

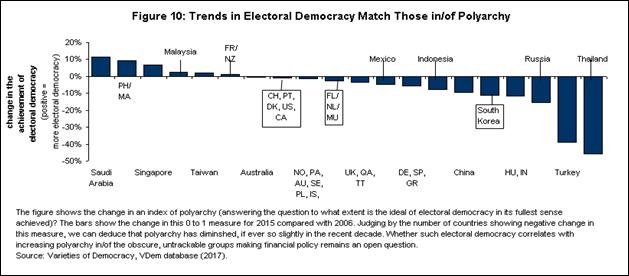

Other evidence seems to point toward polyarchy helping more competitive international financial centres than less competitive ones. Figure 9 shows the correlations between polyarchy and IFC competitiveness for specific jurisdictions. If each metropolitan financial centre reflects the polyarchy and IFC competitiveness of its host jurisdiction, Singapore and New York, in this sample, had increasingly polyartic institutions with increasingly competitive international financial centres.[96] Jurisdictions from Jakarta to Budapest had decreasingly polyartic political participation, perhaps in a bid to increase their financial centres’ competitiveness? Figure 10 bolsters such an interpretation by looking at how the achievement of electoral democracy has responded in various international financial centres in response to the global financial crisis – or visa versa.[97] Naturally, the extent of polyarchy (and possible electoral democracy) would affect the economic response to the crisis – and thus the ranking of a jurisdiction’s international financial centre.[98] Yet, as with most social economic questions, the converse might also hold. The crisis – and thus an international financial centre’s competitiveness -- affects the extent of polyarchy.[99] More participation in many cases means a replacement of incumbents, rather than an increased diversity of voices and preferences at the political bargaining table.[100] Regardless of which way causality lies, polyarchy and the size/growth of international financial centres affect each other.

The centrality of a financial centre among the flow of funds in the network of international financial centres best measures an IFC’s competitiveness. Academics have long theorised about – and even mapped -- the networks of financial capital flowing across/between international financial centres.[101] Such network maps have included measurements of financial centres’ degree of linkage, betweeness and other network statistics common to all graphs.[102] Such network measurements have allowed academics to measure things like the extent of systemic risks to the entire global banking system.[103] In such a network, geographic distance and physical centrality matters far less than network centrality.[104] Figure 11a for example shows the changes in polyarchy and changes in international financial centres’ clustering coefficients (or the extent to which a jurisdiction connects its banking partners without these other banking partners necessarily having linkages between themselves). More polyartic international financial centres cluster more with other financial centres, as measured by their clustering coefficient (basically a measure of their centrality importance in the international financial centre network).[105] Figure 11b shows the same data – fit to a non-linear curve instead of a simple line. Such a curve suggests that polyarchy increases in/for weakly and strongly clustered international financial centres. Singapore represents an increasingly important (as measured by its clustering coefficient) jurisdiction becoming more polyartic over time. Japan’s clustering coefficient rose, while polyarchy fell. The trend seems to show that polyarchy remains stable for jurisdictions losing importance over time (like Austria and Canada). Does a stable, equilibrium-level of polyarchy correspond with ever-decreasing clustering importance? Or put conversely, do some jurisdictions need to become more polyartic before they can gain network centrality?

Without controlling for other factors like macroeconomic fluctuations and the demand for capital, the network data seem to display contradictory trends. Figure 12 shows the relationship between international financial centres’ authority (or the extent to which other financial centres place money with their banks). Over the period we studied, international financial centres’ authority decreased as polyarchy in these international financial centres rose.[106] Some might argue that highly connected financial centres feel crises and other large changes in their competitiveness less – attenuating the need for the polyarchy which helps boost competitiveness.[107] Others argue that regional links have replaced global links.[108] Yet, without controlling for other factors though, these data could say anything (or nothing at all). Other factors likely interfere too badly for us to draw any conclusions about these data.

Modelling

and Operationalizing Endogenous Change in IFC Politics and Competitiveness

Changes Within and Between Countries

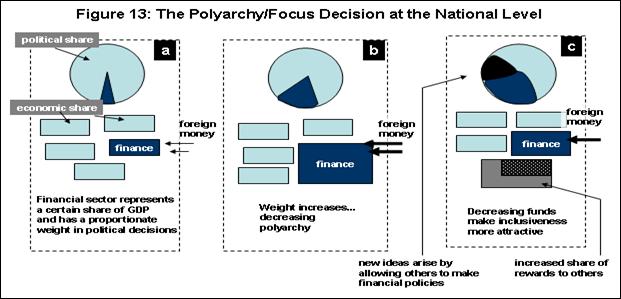

Our model focuses on

the trade-off between political rights and economic power in international

financial centres. Figure 13 shows a simplified, non-mathematical, graphical, static

version of our model. In the left-most side of the figure (part a), we depict

various sectors of the economy (as blocks) and their relative political power

as the circular pie at the top. We highlight the financial sector as the dark

blue box, whose size depends on cross-border banking liabilities (deposits and

funds from abroad). The dark blue slice of the pie represents finance’s weight

in political decision-making. In part b of the figure, we observe the financial

sector’s increased importance (share) in/of political decision making,

concomitant with its current, future, or even perceived ability to

attract capital from abroad.[109]

Such a trend might correspond with an increased focus on financial policy (and

thus decreasing polyarchy in order to implement financial policies rather than

other policies).[110]

Similar decisions in other jurisdictions negatively impact on the size of the

home jurisdiction’s financial institutions (depicted in the figure’s part c) as

a shrinking in size compared with part b. In part c, the financial sector’s political

power (concentration of influence) shrinks, yielding way to other sectors with

better/different ideas – as depicted by the black coloured slice of the

political pie. Other sectors’ inclusion in policy making increases as does

their inclusion in the economy (as shown by the larger size of non-finance

sectors).

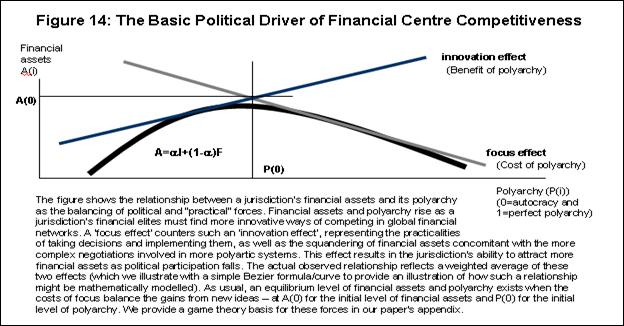

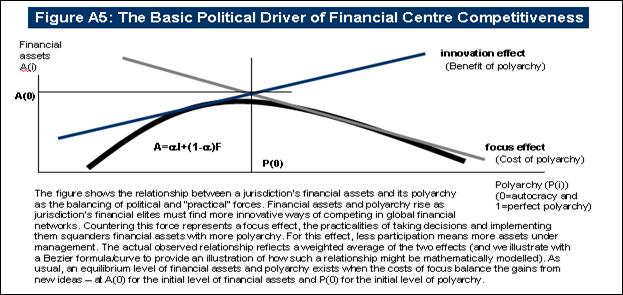

In slightly more

mathematical form, the amount of cross-border financial assets and polyarchy in

a jurisdiction depends on the focus/concentration of policy on finance and the

creation of new ideas and innovations in finance, ideas which will help attract

funds from foreign financial centres. Figure 14 shows the simplest possible

representation of these factors. In theory, more polyarchy brings more

innovation, from access to more ideas and high-powered interest in finance’s

success – as represented by an upward sloping innovation effect curve.[111]

At the same time though, more polyarchy diverts time, attention and political

capital away from finance – as shown by a decreasing focus curve. The mix

between these forces decides the level of cross-border financial system

liabilities and the level of political polyarchy – and both forces work at the

same time.

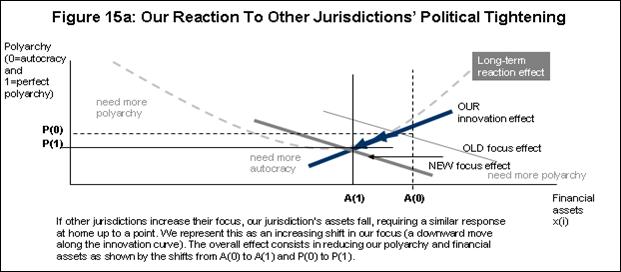

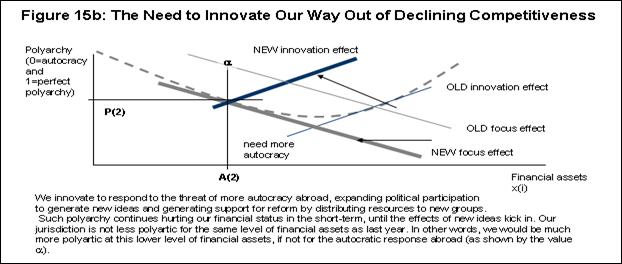

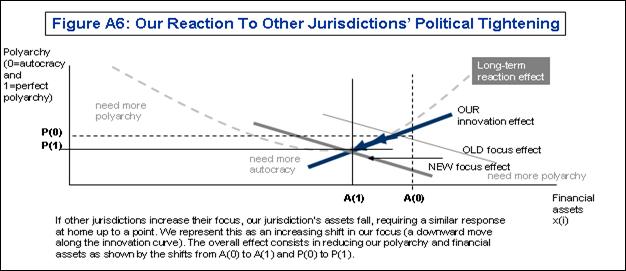

These curves allow us

to examine the impact of other jurisdictions’ changes in policy. Figure 15a

shows the effect of an increase in the focus of financial policies and politics

in one of the jurisdiction’s main counterpart jurisdictions (for example the

effect in France of the UK focusing on financial policy and Westminster’s deafening

to health and other policies).[112]

Such a policy – according to our model – would shift out the focus effect curve.

The move (and we flipped the axes to

make the figure focus on changes in financial assets) results in a decrease in

polyarchy and a fall in financial assets – as the home jurisdiction matches

this focus and loses business to the more focused rival. Figure 15b shows the

effect at home of these changes – as local political and economic forces encourage

more participation. A shifting out of the innovation curve represents the

effect of local financiers looking for new, innovative ideas from sectors

formerly muted out, and other sectors looking for recompense for their previous

patience. Such an internal shift further undermines foreigners’ confidence in

placing their money with our financial institutions.[113]

Such a decline would have – in the past – represented the simple redistribution

of political power and economic fortunes (as shown by point a in the figure lying along the previous focus curve).

Because our counterpart jurisdictions have increased their focus on becoming

world class financial centres, we can extend our own polyarchy far less than

before in order to remain competitive... at least in this middle term.

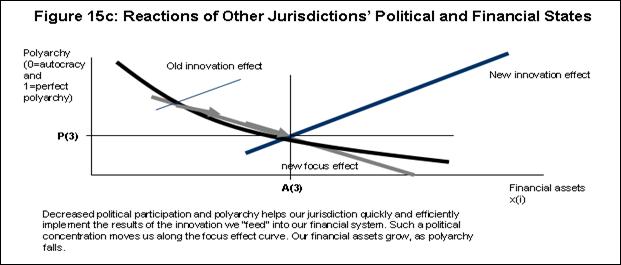

In the longer-term

though, polyarchy and financial assets held by our financial institutions

settle at an equilibrium point dictated by finance-related tastes and

technologies. Figure 15c shows the increase in financial assets and the

accompanying decrease in polyarchy from its temporary very high levels, as

financial services firms implement innovative ideas. Figure 15d shows the same

relationship between these variables as in Figure 14, though with the figure

turned on its side. The figure shows an adjustment path as other jurisdictions

change their polyarchy and/or financial assets (and thus their centrality in

the international network of financial centres). The levels A(4) and P(4)

represent those post-adjustment, equilibrium values.

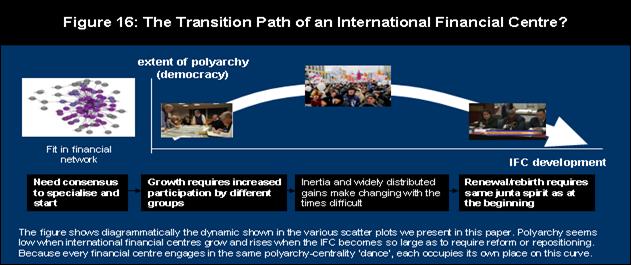

Because each wave of

innovation leads to larger, more developed financial services firms, we can

hypothesize about the way polyarchy changes as a financial centre develops.

Figure 16 shows that conjectured change. As a financial centre seeks to grow, a

pushing/guiding political force discourages dissent and encourages foreign

investment. Experiences from the UAE, Singapore, and Qatar represent the most

mediatised examples.[114]

In other cases, the lack any traditional means of economic development --

combined with a geography that gave finance a natural competitive advantage - encouraged

an autocratic political focus on finance.[115]

While many international financial centres still make finance a core area of

policy, many have started opening to other areas. To what extent does such an

opening represent a way of invigorating finance – rather than an attempt to

diversify the local/national economy? Only time will tell.

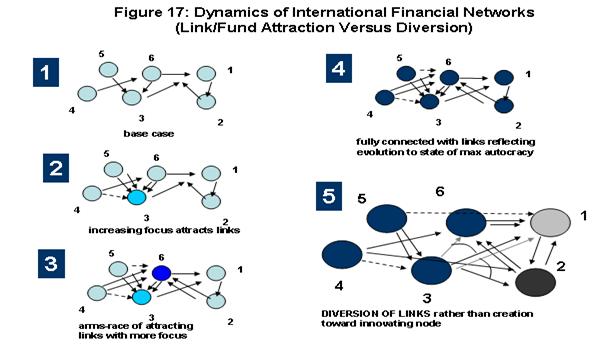

Changes over Time

In our model, international financial centres grow over time, as they focus on finance. Figure 17 shows the mental model we used to develop our model. In plate 1, we see 6 financial centres represented as a simple set of nodes. In plate 2, we show the situation where financial centre number 3 focuses on developing its financial centre. As we described in the literature review, and showed in the previous empirical overview section, such a policy-focus leads to more links and more financial assets travelling along those links.[116] As plate 3 shows, as other financial centres focus even more intensively on finance, they build out both the quantity and depth of these network links.[117] As we described in the literature review, historically one financial centre developed and grow because of growth in counterpart centres. The self-reinforcing network of financial centres grows as more and more centres decide to develop their financial centres and linkages.

The figure shows the dynamic effects of an increase in

focus (a decrease in polyarchy) for theoretical financial centres in a

theoretical network. The light blue node (number 3) indicates an exogenous

change toward more focus. The darker blue node (number 6) indicates more

focused policies than those pursued by node 3 (simulated possibly as a random

reaction to node 3’s policy). As more nodes focus their financial policies, the

number of links increases. Plate number 4 shows the results of this race to the

bottom, where all nodes have the maximum number of links. Similarly, in plate

5, the light gray node (number 1) represents the introduction of

innovation-producing polyartic policies. The dark gray node (number 2)

represents a jurisdiction introducing more polyarchy than in node 1. The cycle

reverses itself, except such increases in polyartic policies cause links to

divert from other financial centres (preserving the total number of links in

the system). One could imagine/model an intermediary situation, where some

nodes decrease their polyarchy, while others increase such polyarchy (thus

avoiding the all-of-nothing wave-like patterns we have shown in this simple

example).

As some financial centres fall behind, they engage in the innovation needed to develop new markets, new ideas, new financial products and new markets. New innovations do not always require democracy (increased polyarchy). An increase in polyarchy does not guarantee financial innovation. Places like Singapore and Shanghai have developed for a long time without such polyarchy. In our model, such polyartic-led innovation results in a shift in financial links – a diversion of funds from other centres.[118] Polyarchy changes the relative distribution of resources – allowing for future concentration.[119] Yet, in the short-term, innovation only serves to give other financial centres time to further focus their policy priorities toward finance.

The

Data and Empirical Methods We Used

Jurisdictions, raw polyarchy and network centralities

In order to test our theories, we first had to compile the relevant data for the relevant jurisdictions.

Figures 18 provide an overview of the data we used. Figure 18a show the jurisdictions in our study, while Figure 18b shows the average values of polyarchy and eigencentrality from 2005 to 2015 – before being adjusted for the way that macroeconomic and other factors affect them. Figure 18c shows the extent to which aggregate polyarchy has changed (fallen) over the years when compares with jurisdictions’ eigencentrality. . Figure 18d shows the networks of financial relations between international financial centres in 2005 and 2015. Grouping these networks in modules, we see increasing concentration over time (matching other data).

|

Figure 18d: Financial Networks in 2005 and

2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

The figure shows

the network of cross-border bank liabilities in 2005 and 2015, sorted by the top

major groupings of financial centres. Such “modularity” (as the statistical

name for such grouping) results from closer links between module members than

the rest of the network. Such modularity changed radically over the 10 years.

In 2015, top groupings accounted for 56%, 39% and 3% respectively for the top

three modules. In 2015, the top grouping accounted for 63%, 20% and 10% of

all financial centres (with 3 more groups scoring the remainder). These

networks became thus more concentrated over time. |

|

The way that polyarchy affects the amount of cross-border liabilities that banks can attract has decreased over time. Figure 18e shows the slope of a line of best fit between polyarchy and cross-border bank liabilities placed by each jurisdiction’s largest counterpart jurisdiction. For example, in 2005, on average, a one point increase in polyarchy in any particular jurisdiction (like France) resulted in that jurisdiction’s main counterpart (like the UK) placing roughly $18 million in extra cross-border liabilities in that particular jurisdiction (France). The values in the black boxes show

the way ‘drop off’ in each jurisdiction’s counterpart’s cross-border liabilities changes for a one point increase in that jurisdiction’s polyarchy. We define such a ‘drop-off’ as the proportional difference in the value of cross-border liabilities from lower ranked jurisdiction counterparts. For example, France’s second largest counterpart jurisdiction (the US) may provide 12% fewer cross-border bank liabilities than the first ranked jurisdiction (the UK). Similarly, on average, France’s third largest counterpart jurisdiction provided 12% fewer liabilities than the US. The value in the black boxes in Figure 18e do not represent the value of such a drop-off. Instead, they measure the way that drop-off value changes as polyarchy in a jurisdiction rises.[120]

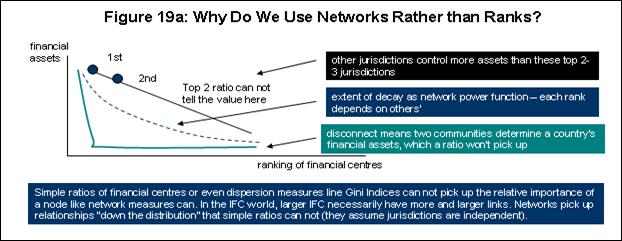

One approach to analysing our bank liabilities data might consist of looking at the ranks of cross-border bank liabilities between these financial centres. We might devise some method – like a ratio of largest to smallest counterpart jurisdiction – or some measure the deviations from the average. Figures 19 explains why we used network characteristics instead. In brief, we used network characteristics because of the dependencies between the financing partners themselves. As Figure 19a shows, the construction of any ratio of even deviation from average assumes that one observation (country’s data) do not depend on other countries. We can construct a reliable ratio (for example) if the denominator partly changes every time the denominator does. As Figure 19b shows, if we compare financial centres’ network centralities with entropies (a measure of the similarity of each partner’s bank liabilities), we see little relationship at all (as shown in the scatter plot in the lower left hand side of the figure). Figure 19c describes the term eigencentrality we use throughout this study.

Figure 19c: What is Eigencentrality? As we describe

in the appendix, eigencentrality refers to the importance of an

international financial centre in the network of such financial centres.

Such centrality takes into account the value of cross-border bank

liabilities a jurisdiction attracts from counterpart jurisdictions. Such

centrality also takes into account the importance of that jurisdiction’s

partner countries for their own counterparts. The eigencentrality algorithm

basically traces the value of all these liabilities across the whole

network of financial centres for all jurisdictions. The most central

jurisdictions attract large amounts of cross-border liabilities from

jurisdictions which attract a large amount of these liabilities and so on

all the way through the network. The German word eigen means

characteristic (as in a physical or identifying characteristic). Such a

procedure thus finds the true or characteristic values of these

jurisdictions by already including the potential investments/liabilities

other financial centres indirectly make to that jurisdiction through its

networks of partners. Eigencentrality thus truly provides a

financial-system-wide view.

Figure 20 shows the variables we used in our study. The dependent variables consist of polyarchy in each jurisdiction as well as two measures allowing us to quantify the nature of each jurisdiction’s financial networks. In order to compare polyarchy and a jurisdiction’s centrality in international financial centre networks, we had to control for non-political factors. For example, a jurisdiction could attract large amounts of cross-border bank liabilities because of favourable exchange rates or because its government requires more funding to operate public services (and they want to use foreign funds/deposits to finance such funding).

Figure

20: List of Variables Used to Remove the Effect of Macroeconomic and Other

Variables When Estimating the Amount of Cross-Border Bank Liabilities

|

Factor |

N |

Mean |

Std.

Dev |

Min |

Max |

Diff? |

|

Dependent Variables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Polyarchy |

192 |

85.06 |

12.45 |

9.21 |

94.71 |

* |

|

Largest ‘investment’ partner |

181 |

231776 |

355,563 |

1406 |

2,002,814 |

* |

|

Power Law |

181 |

-0.3 |

0.1 |

-0.63 |

-0 |

* |

|

Macro push/ pull factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real

effective exchange rate index† |

180 |

99.03 |

7.95 |

70.9 |

125.7 |

* |

|

Real

interest rate (%) |

140 |

5.28 |

8.56 |

-10.8 |

44.6 |

|

|

Attraction Factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Market

cap. (% of GDP) |

150 |

93.94 |

61.16 |

17.57 |

282.51 |

* |

|

GDP

per capita, PPP (current thousands international $) |

192 |

37.4 |

14.56 |

4.77 |

129.34 |

* |

|

S&P

Global Equity Indices (annual % change) |

192 |

7.13 |

29.27 |

-69.94 |

125.11 |

|

|

Current

account balance (% of GDP) |

192 |

1.35 |

5.44 |

-7.51 |

31.06 |

|

|

Commercial

service exports (current billion US$) |

192 |

116.45 |

134.74 |

5.58 |

730.59 |

* |

|

Connectivity factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Air

transport, millions of passengers carried |

172 |

89.23 |

172.36 |

0.55 |

798.22 |

* |

|

Demanders of funds |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Central

government debt, total (% of GDP) |

160 |

60.65 |

26.52 |

18.37 |

132.36 |

* |

|

Gross

capital formation (% of GDP) |

192 |

23.07 |

4.14 |

14.73 |

43.26 |

|

|

Suppliers of funds |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gross

domestic savings (% of GDP) |

192 |

26.03 |

8.08 |

12.47 |

75.54 |

* |

|

FDI,

net inflows (% of GDP) |

192 |

6.22 |

11.35 |

-5.63 |

87.44 |

* |

|

Broad

money growth (annual %) |

116 |

8.50 |

6.66 |

-25.5 |

22.05 |

|

|

Institutional factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rule

of Law‡ |

190 |

1.35 |

0.78 |

-0.66 |

2.10 |

* |

† 100

=2010

‡

rule of law comes from the World Bank’s Governance Indicators for the variable

by that same name. All the other variables should be self-explanatory.

Diff?

refers to whether we calculated and used annual differences in this variable.

Without controlling for macroeconomic and other factors, our analysis would have been badly biased. The previous figure (Figure 20) shows the five (5) factors that we grouped these variables into.[121] Macroeconomic push-pull factors include variables that could push or pull funds across borders to a jurisdiction’s banks. Exchange rates and interest rates represent self-explanatory variables.[122] Attraction factors represent variables that might attract foreign funds (the size and performance of local stock markets, the need to finance trade, and the overall jurisdiction’s wealth/size.[123] Air transport represents our only factor measuring the jurisdiction’s connectivity.[124] Demanders of funds – like government and business investment – draw out demand for foreign funds.[125] Suppliers of local funds might help crowd out (or crowd in) foreign funds.[126] These suppliers include households and their savings, foreign direct investment and credit growth by/from the central bank.[127] Finally, no analysis is complete these days without a consideration of local institutions and the quality of regulations (as proxied by the World Bank’s Governance Indicators variable measuring the rule of law).[128]

Getting polyarchy and network centralities ready for

analysis

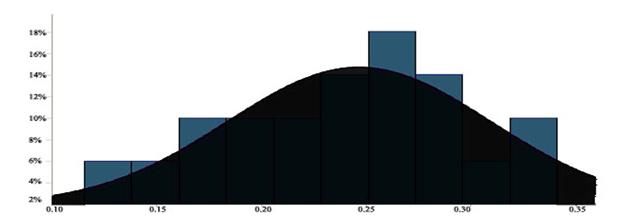

Macroeconomic and other factors correlate heavily with the polyarchy and centrality of international financial centres. Figure 21 shows the number of variables, combinations of these variables, and non-linearities in these variables which correlate with their jurisdiction’s polyarchy indices.[129] About 80% of all these combinations statistically significantly correlate with polyarchy at a 95% level of confidence or better. These data show that we must remove their effects before trying to find patterns related to these international financial centres’ centrality in their financial networks. Figure 22 shows the general process we used to strip away the effects of these macroeconomic variables – on both polyarchy and eigencentrality values. We regressed these variables (the covariates) on polyarchy and eigencentrality values using panel methods – in order to arrive at “pure” polyarchy and eigencentrality values.[130] As Figure 23 shows though, we had to correct the data for the interdependencies between them. The left side of the figure shows two completely independent factors (regression requires such independence to “work correctly”).[131] We see many variables clumping nearer to each other than these independent axes (known as eigenvectors). The correlation matrix on the right side of the figure further shows such interdependences between these variables. A bit fewer than half of all these variables statistically significantly correlate with each other. Without correcting for such inter-correlation, we would accidently assign part of the effect of exchange rate movements on trade balances, to cite one of the many ‘multicollinearities’ (as economists refer to such a problem) in these data.

|

|

The

figure shows the variables which statistically significantly correlate with

polyarchy across years and countries. We found these correlations using a

technique known as response surface regression. Such a technique looks for

non-linearities and interactions between variables. A computer normally could

not solve such a large system of equations. We used a particular robust

technique known as a recursive power method to find very microscopic values

of our matrix when inverting the matrix to find a solution. The techniques we

used are less important than the general message. Most of the variables in

our study statistically significantly correlate with polyarchy – interfering

with any analysis trying to spot the effects of a jurisdiction’s network

centrality on such polyarchy. We could show similar results for network

centrality – that these variables affect the extent to which financial firms

attract cross-border bank liabilities. Such multiple correlation would interfere

with any attempt to look directly at the relationship between jurisdictions’

polyarchy and network centrality. We describe below how we removed the

influence of these factors from our analysis. |

|

Figure 23: Fixing Problems That Arise When

Variables Correlate With Each Other (Multi-collinearity) |

|

|

|

|

|

The

figure shows the extent to which the covariates we try to control for correlate

with each other. Such correlation (called multi-collinearity) causes any

analysis of one variable (like government debt) to pick up the effects of

other variables like market capitalisation, trade balances, popularity as an

air travel destination and so forth.

The left part of the figure shows the relationship of our variables

with two completely independent variables (called orthogonal factors). Ideally, we need our variables to sit on

one of these axes. The right hand side shows the correlation coefficients

between the variables we used to adjust our polyarchy and network centrality

data. The coloured cells show the correlations with a 95% probability or

greater of statistically significantly varying with each other. Source:

authors calculations (with data from the Bank for International Settlements,

2017). |

|

The resulting analysis yields the ‘predicted values’ of our key variables of interest. Regressing a jurisdiction’s bank liabilities on exchange rates, government debt, air travel and other factors yields a predicted value for these liabilities. The model’s error thus reflects the part of these financial flows unexplained by these macroeconomic and other factors. We use these errors as our estimates/variables of ‘pure’ cross-border bank liabilities (after controlling for these other factors). Figure 24 provides one example of how we estimated the largest liability flow from each jurisdiction’s largest counterpart for one year (in 2005). The figure shows the actual values of these liabilities, their predicted values from our model, and the differences between the predicted values and actual values. Figure 25 shows the extent to which the values of bank liabilities for the second, third, fourth and other partner jurisdictions “drop off” (decrease in value) by rank. Such a drop off – combined with the largest finance partner – provides the new structure of financial networks.[132]

The figure shows the relationship between actual

cross-border bank liabilities from each country’s largest cross-border

counterpart and those predicted by the best fitting model. For example, in

2005, the largest value of Australia’s cross-border bank liabilities came from

the US. We estimate this predicted value for each country, for each year, in

order to estimate how funds would have flowed between international financial

centres if we could remove the effects of variables like real exchange rate

changes, GDP growth, the level of government debt, and so forth. We show a

simple linear regression here to illustrate the general idea. In practice, we

used a machine learning model (which actually did not deviate too much from

this simplistic model).

The figure shows the predicted “drop off” in the value

of bank liabilities for each of the countries in our sample. We calculate such

a drop off by sorting the value of bank liabilities coming from each

jurisdiction’s partner jurisdictions, and then fitting an exponential function

to these values. For example, the value of each of Australia’s counterpart

jurisdictions decreased by 35% when sorted from largest counterpart

jurisdiction to smallest. We show the linear predicted value of these ‘drop-off’

values in the figure to illustrate our broader methodology. We used a machine

learning algorithm to fit the actual values (though these values came pretty

close to our more complex method).

We constructed ‘pure’ financial networks for these cross-border bank liabilities by combining these new largest partner estimates with these new drop-off estimates. Figure 26 shows how we constructed these new networks – using Australia’s cross-border bank liabilities from 2005 as an example. If Australia’s largest provider of funds in 2005 held $35 million in assets (recorded on the Australian side as a liability), then our cross-country econometric estimation predicted a value of $106 million – assuming exchange rate movements, different government debt levels, and other factors had not affected these funding patterns. By rank, each counterpart jurisdiction placed 35% fewer funds with Australian banks than the one ranked ahead it. After controlling for these macroeconomic and other effects, they should have placed 29% less – in effect investing more per partner jurisdiction.

The figure shows how we adjusted one country’s

(Australia’s) cross-border bank liabilities for exchange rate movements, GDP

sizes, government debt stocks and the other factors we have previously

described. The black line shows the value of Australia’s cross-border bank

liabilities coming from its largest partner jurisdiction (the US) as roughly

US$35,000 in 2005. The next largest value of these bank liabilities came from

the UK and represented about 35% less than cross-border bank liabilities from

the US – and so forth down the line of partner jurisdictions. The predicted

value of Australia’s bank liabilities (‘removing’ the effect of all these

outside variables) came to about US$106,700 for the largest partner (again the

US), with the US and other jurisdictions’ cross-border bank liabilities’ values

decreasing by about 29% when sorted by size. Note that we used the residual of

the regression to find these values – not the predicted values themselves.

Such differences in these financial centres’ leading financial partner and the extent to which such financing drops off by rank leads to different network configurations, after going through this exercise for all the financial centres in a particular year.[133] Figure 27 shows the network of these bank liabilities in 2010, before adjusting for the effects of these macroeconomic and other variables – and after. Australia’s and South Africa’s centrality would have increased remarkably. Places like Jersey would have lost out a bit.[134] Figure 28 summarises these changes – showing the way mean values would have changed.

|

Figure 27: The Network of Cross-Border Bank

Deposits and Other Liabilities for International Financial Centres Before and

After Adjusting for Macroeconomic and Other Variables |

|

|

|

|

|

BEFORE ADJUSTMENT |

AFTER ADJUSTMENT |

|

The

figure shows the network structure (geography) of cross-border bank

liabilities for the most important international financial centres for 2010

(as one example from 2005 to 2015). For negative values of these flows, we

switched the direction of these flows, from destination to source (rather

than the other way around). We calculated each country’s eigencentrality from

networks like these for each year from 2005 to 2015. These eigencentralities

measure the importance of an international financial centre, taking into

account the size of cross-border bank liabilities its counterpart

jurisdictions attract from their own partner jurisdictions. The final

eigencentralities thus exclude the effects of macroeconomic and other factors

we used in our preliminary regressions. |

|

Figure

28: Summary Statistics for Polyarchies and Eigencentralities Used in Study

|

Variable |

Valid N |

Mean |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Std.Dev. |

|

Pure Polyarchy |

160 |

18.81 |

0.0 |

119.38 |

11.15 |

|

Difference in Pure Polyarchy |

141 |

0.74 |

-7.5 |

45.51 |

5.27 |

|

Voice |

192 |

114.83 |

-170.0 |

173.96 |

55.87 |

|

Difference in Voice |

163 |

-2.05 |

-162.3 |

91.89 |

19.48 |

|

Old eigencentrality |

128 |

90.79 |

0.0 |

100.00 |

11.97 |

|

New eigencentrality |

156 |

37.80 |

8.7 |

100.00 |

33.28 |

|

Change in new eigencentrality* |

130 |

63.68 |

-10000.0 |

10000.00 |

3646.91 |

|

Invest Entropic Measure * 100 |

184 |

15.91 |

6.7 |

54.26 |

8.56 |

The figure shows

the differences in the values of our variables, before and after controlling

for outside factors. “Pure” variables refer to variables calculated as the

‘error’ or residual of the regression analysis we described earlier, adjusting

for the effects of macroeconomic and other factors. We provide data for voice and entropy, two

variables which we will discuss in more detail as we test the robustness of our

analysis.

* We rescaled

these changes to maintain the same scale as the other data.

Changes over time

Even after finding the “pure” values of polyarchy and eigencentralities, we still need to make sure that any correlation between these variables does not arise from inertia. If a country’s polyarchy in any year depends mostly on such polyarchy in the previous year (or years) before, then such a dependence on the past can block out any attempt to correlate such polyarchy with the network importance of the jurisdiction and its partner/competitor jurisdictions. Figure 29 shows the extent of such inertia – which economists call auto-correlation – for select jurisdictions’ eigencentrality and polyarchy. We observe no value approaches one (1) – the value at which last year’s polyarchy equals this year’s polyarchy.[135]

We can then look at how each country’s polyarchy-eigencentrality adjusted over the decade. Figure 30 shows some examples of our data. The left hand side of the figure shows Australia’s polyarchy compared with its own eigencentrality. We observe a hill-like pattern in this one example of Australia’s polyarchy compared with the jurisdiction’s own eigencentrality.[136] Australia’s eigencentrality and polyarchy have risen together for lower levels of the country’s eigencentrality. As Australia gains prominence in global international networks, polyarchy fell. We similarly show one example of the way Australia’s polyarchy changed as Denmark’s eigencentrality changed in the right part of the figure. In this particular outcome, Australia’s polyarchy increased as Denmark eigencentrality rose. The trend on the bottom of the figure shows the way that Australia’s polyarchy responded to a change in its eigencentrality – for various levels of its eigencentrality. Such a figure – called a ‘spider plot’ – shows the way that polyarchy reacts to a jurisdiction’s eigencentrality over all possible states of these variables.

The “spider” graph in the last part of the figure shows a similar trend – adjusting for the randomness of these variables. Namely, this spider graph shows the results over 1,000 simulations – ensuring that the final relationship roughly depicts the relationship without very wide confidence intervals leading away from this line. Yet, this method of analysis treats different observations from different years as random draws from a deeper relationship between these two variables. Such a procedure gives a snapshot picture, by using data collected over time.

|

Figure 30: The Relationships Between Polyarchy

and Eigencentrality (Actual and Bayesian) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The figure shows

the relationship between Australia’s polyarchy and eigencentrality from 2005

to 2015 as an example of the methods we used in this study. The top left

panel shows a simple correlation of these variables for Australia. The top

right panel shows the simple actual correlation between Australia’s polyarchy

and Denmark’s eigencentrality. The bottom curve – called a spider plot –

shows the conditional mean of the way Australia’s polyarchy changed for

changes in its eigencentrality, over various levels of such eigencentrality.

In this figure, changes in Australian polyarchy, compared with changes in

eigencentrality rose when Australia did not occupy too central a position in

global financial networks (ie possessed low eigencentrality). Such polyarchy

increases the slowest at medium levels of eigencentrality – supporting the

model we presented in the previous section of our paper. The figure shows the

relationship over 1,000 simulations – and does not change when we rerun the

simulations (namely we have a consistent parameter). Think of the figure as

fitting regression lines on polyarchy and eigencentrality when dividing

eigencentrality into sub-samples by size.

|

|

We should explain further the importance of the spider plot. If the top part of Figure 30 shows one realisation of the way Australia’s polyarchy changed as the jurisdiction’s eigencentrality changed from 2005 to 2015, we could imagine “alternate universes.” We could imagine these data come from distributions which we can not see. We saw these data – but we could have easily seen other data too. The spider plot presents a Bayesian analysis of these variables. We resampled randomly 1,000 times from the historical data and the likely distribution generating these data.[137]

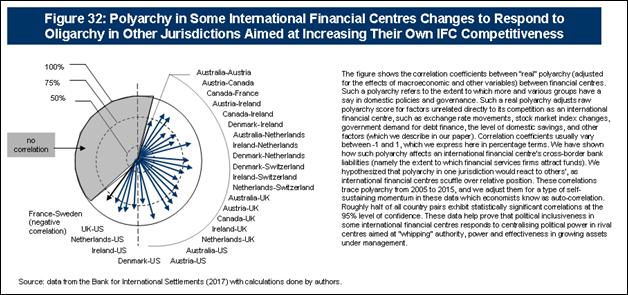

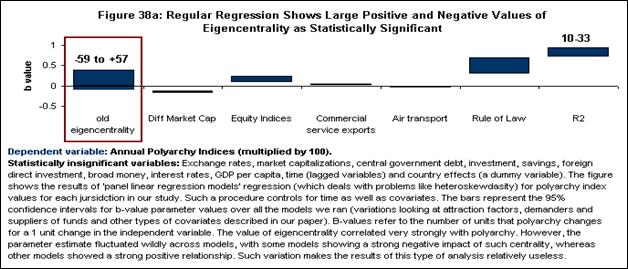

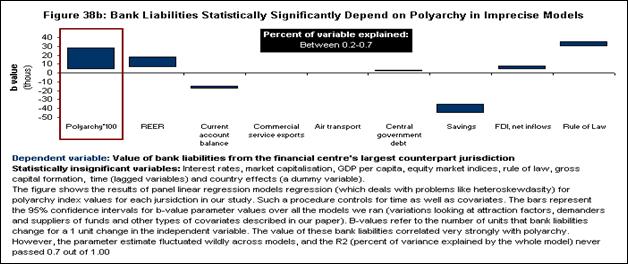

Over all these samples, we obtained the stable relationship between the way polyarchy changes compared with eigencentrality – for various levels of eigencentrality. Such analysis allows us to see how polyarchy might change its response, as eigencentrality changes. We could (and do!) conduct similar analyses for all pairs of polyarchy and eigencentrality between international financial centres – providing a detailed map of political change in response to financial competitiveness.